Foreword

Due to the spread of Covid19, we will probably remember 2019 as the year of the pandemic, but it was a year of rebellion as well. A few months before the virus emerged, people in many countries all over the world revolted against their governments’ policies of austerity. The neoliberal governments that promised prosperity and development to their citizens, provided the majority with nothing but destitution. Needless to say, lack of an alternative to the neoliberal system condemned the rebellions to fail miserably.

Also 2019 was a year of social conflict films. Many films depicted the huge class gaps in societies and their subsequent and consequent struggles and dangers. Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won the Palme d’Or and the Oscar for the film of the year, Just 6.5 became the highest grossing non-comedy film in the history of Iranian Cinema, and The Platform totally blew away the moviegoers. But it was probably Todd Phillips’ Joker that sparked the most heated controversies. Some – such as Micah Uetricht in an article for The Guardian– saw the film as a revolt against the late capitalist system and called it “a brilliant portrait of a society that has chosen barbarism” over socialism (link in Works Cited) and some others discussed the conspiracy theories surrounding the film; Shaibal Chhotray, for instance, claims that Joker was “not an anti-capitalist, anti-rich, pro-anarchy take on the current global scenario” and called it “simply a comic-book origin film” (link in Works Cited).

These two extreme viewpoints, we claim, are not helpful enough in understanding the film because they neglect the enchained, ideological aspects of cinema and also the emancipatory inner tension of films. These narrow understandings of cinema as an art form have led to such one-dimensional interpretations that cannot connect the readers to the reality of cinema or politics in the modern world. We claim that Joker, like any other film, is bound to the ideology of the system that produces it, yet the tension lying within the art of film keeps some spots out of reach which allow the contradictory interpretations. In other words, the claim the writers make here is that although this film is not an anti-capitalist one, it can give us some hints as to overcome capitalism by reminding us of some of the flaws in the system and some suggestions. Hence, this article tends to read this film in a different way that can help us have a better understanding of the film and rethink our real world politics.

Although Joker lends itself to many approaches and welcomes different interpretations, the first part of this article attempts to present a political understanding of the film by brief aesthetic, psychoanalytic, and cultural readings to support our claim. In the second part, first the Jokerism that has prevailed in the real world since the film premiered is discussed; then, the writers share their views on what people can do to make changes in the world to their own benefit.

Poetics of Joker

In Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Fredrick Jameson argues that since today we cannot set ourselves apart from the system we criticize, our criticism itself becomes a part of the system and, therefore, becomes neutralized. He believes that creating a new form of aesthetics is the solution.

Arthur wins our sympathy in a conventional way. The camera slowly dollies out as Arthur is crying in pain on the ground. Garbage is everywhere around him. The gloomy soundtrack is on.

Aesthetically, this film is no different from a Hollywood classic. A rebellious work of art, first, needs to undermine the aesthetics of the system it revolts against. Joker does not go beyond the conventional Hollywood characterization and stylistics. An instance is when the main character is introduced. The film opens with a character dolly showing Arthur being what/who he is, while the radio news voiceover fills the audience in regarding the setting and context of the film world. A classic introduction! The following sequence is usually supposed to make the audience relate with the character. In Joker’s case, done perfectly! While he is doing his job and harming no one, Arthur is bullied and beaten up by a few villains. The camera slowly dollies out as Arthur is crying in pain on the ground and the gloomy soundtrack is on. Garbage is everywhere around him. Now the title of the film fills the screen: JOKER. The role the title plays here is to say that this is how Jokers are made. Now Arthur wins our sympathy.

This conventionality in style extends throughout the film. But to avoid over-length, only one more example of clinging to the conventions and the traditional form of filmmaking is mentioned. The parts in which tension prevails, such as the chases, are represented in an exciting way as if the film is a Hollywood blockbuster. Again no break from the common aesthetics. Today, the first thing an artist needs to do to create a revolutionary piece of art is to revolutionize the tenets of aesthetics itself. According to what Jameson says and since – as explained above – in terms of narration and form the film comes up with nothing new, the film is not against the system, but a part of the system itself.

Psychology of Joker

Arthur is under psychological treatment. As a schizophrenic person, he is out of touch with reality, lives in the illusions of being a good son to her mother, becoming a comedian, having an intimate romantic relationship, etc. But the most significant element in the film that tempts us to read it psychoanalytically is the absence of the father figure. According to Freudian/Lacanian psychoanalytic theory, the Father is more than the real father. The Father not only regulates the Oedipal relationship between the child and the mother, but also represents the Law, the rules of life in the society. Hence, the Father represents, obeys, and passes down the Law. The logical consequence of the absence of the Father is that the child will not abide by the Law.

Arthur has always had to cope with his father’s absence. The only person that somehow played the role of the father for Arthur was Penny’s boyfriend who abused him as a child. His schizophrenia also provides the ground for illusions in this matter. He is in search of a Father both in reality and his illusions. In his pursuit of the Father, he gets to Thomas Wayne, a politician. Wayne rejects him with a punch in the face. Then Murray Franklin – who in an illusion tells Arthur that he would give everything up to have a kid like him – rejects him, too when he makes fun of him for his tasteless jokes by playing his videos and inviting him on the show. This rejection from the Father, negatively influences Arthur’s adherence to the Law. His revolt against the society and its rules stems from this issue. Through this reading, it can be concluded that the film seems to say that problems with Jokers come from personal issues and relationships, independent of the system and its structural flaws. Therefore, it can be inferred that here again the film is not a rebellious film against the system.

Politics of Joker

The movie is set during the early 1980s, when Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in England were engaged in forcing new policies of austerity and the free market, the ideology currently known as neoliberalism, onto all areas of public life. Neoliberalism, as the name divulges, is a revival of liberalism. This definition suggests that the absence of liberalism, for a period of time, as a political ideology paved the way for the emergence of its recent reincarnated form. In their Neoliberalism: A Very Short Introduction, Steger and Roy define it as “a set of economic reform policies which are concerned with the deregulation of the economy, the liberalization of the trade and industry, and the privatization of the state-owned enterprises” (14). This movement, which was shaped by a network of specific intellectuals and institutions in the Post-WWII era, took its power and validation by selling the lie of engendering economic growth, prosperity and, of course, freedom for all people, and cutting the tyranny of monarchical and aristocratic authorities. Quite opposite, neoliberalism proved to be socialism for the rich minority and austerity for the poor majority.

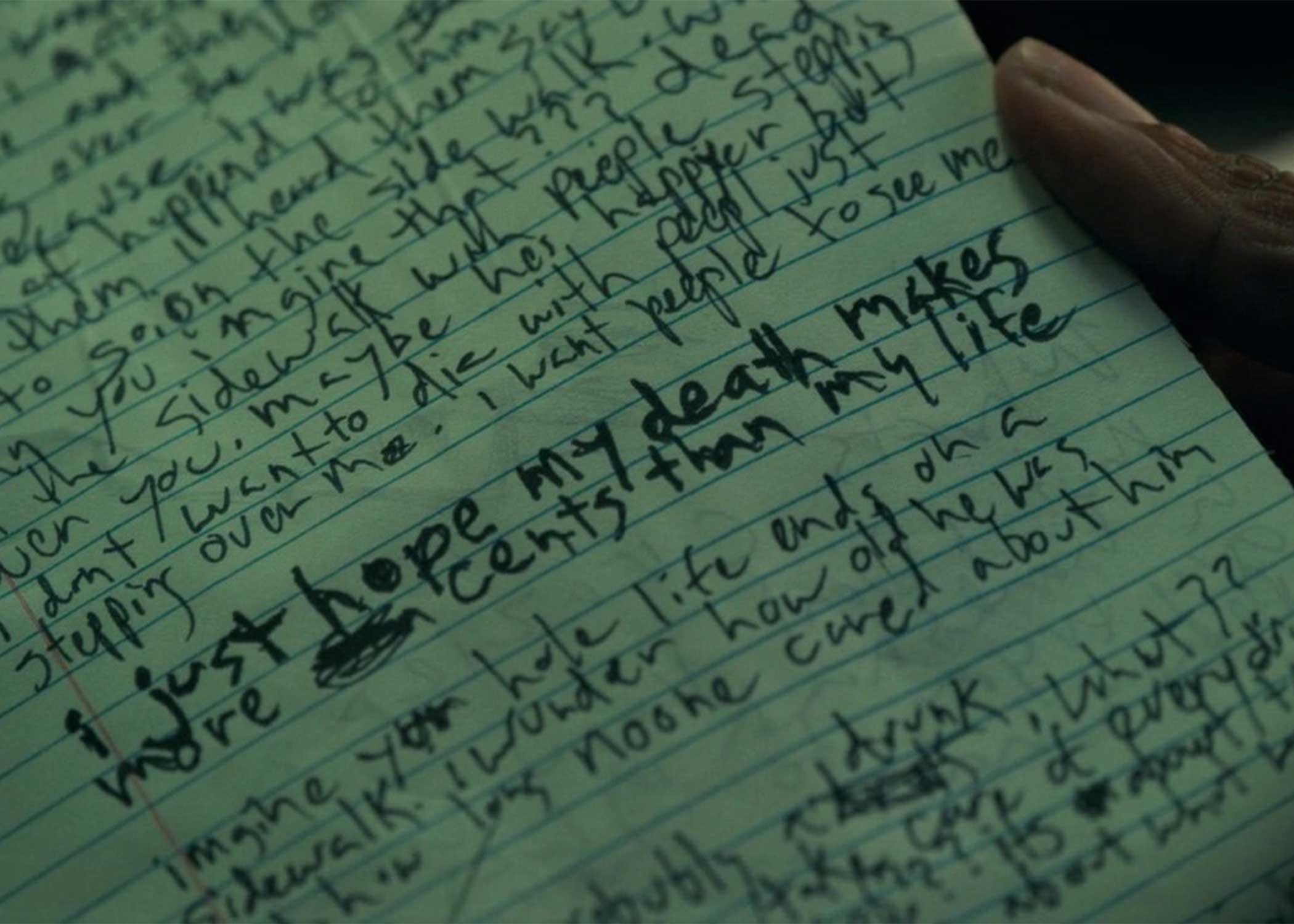

This note in Arthur’s notebook shows his deep financial frustration in a neoliberal society. It reminds us of the unforgettable quote by Willy Loman in Arthur miller’s Death of a Salesman: “Funny, y’know? After all the highways, and the trains, and the appointments, and the years, you end up worth more dead than alive”

Arthur is the representation of the outcome of neoliberal policies. An oppressed, isolated, alienated individual who is mentally ill, lives with his mother in a small apartment in the rotten city of Gotham and is a clown by vocation. He is not paid a living wage for his job as a clown and has been denied public services and mental health care by public hospitals. The economic insecurity, emotional stress, inequality, physical assault, scorn, and many other consequences of neoliberalism are the reasons behind Arthur’s transformation into Joker. The movie opens with Arthur doing his clown makeup while the TV newscaster is warning people about urban blight, the growing piles of literal and metaphorical dirt. The sovereignty and wrecking influence of neoliberalism – and its resultant class conflicts and miseries – over people’s lives is featured through various episodes from news shows (the radio says “The city is under siege by sores of rats”), shots of newspapers (headlines saying “KILL THE RICH”), some references to the sanitation worker’s strike, and the piled up garbage constantly visible on Gotham streets.

An important crisis in the film world is unemployment which is always a problem in neoliberal systems. In the film, “People are upset. They are struggling looking for work. These are tough times.” The insecurity that unemployment brings turns competition into a social law. This is shown in the film when Randall sets Arthur up to take his job. In his Mutual Aid, Peter Kropotkin argues that competition is the law of the jungle, but cooperation is the law of civilization. When Arthur says “Nobody’s civil anymore,” he touches upon the competitive nature of neoliberalism that turns the society into a jungle in which everyone has to compete against the others to survive.

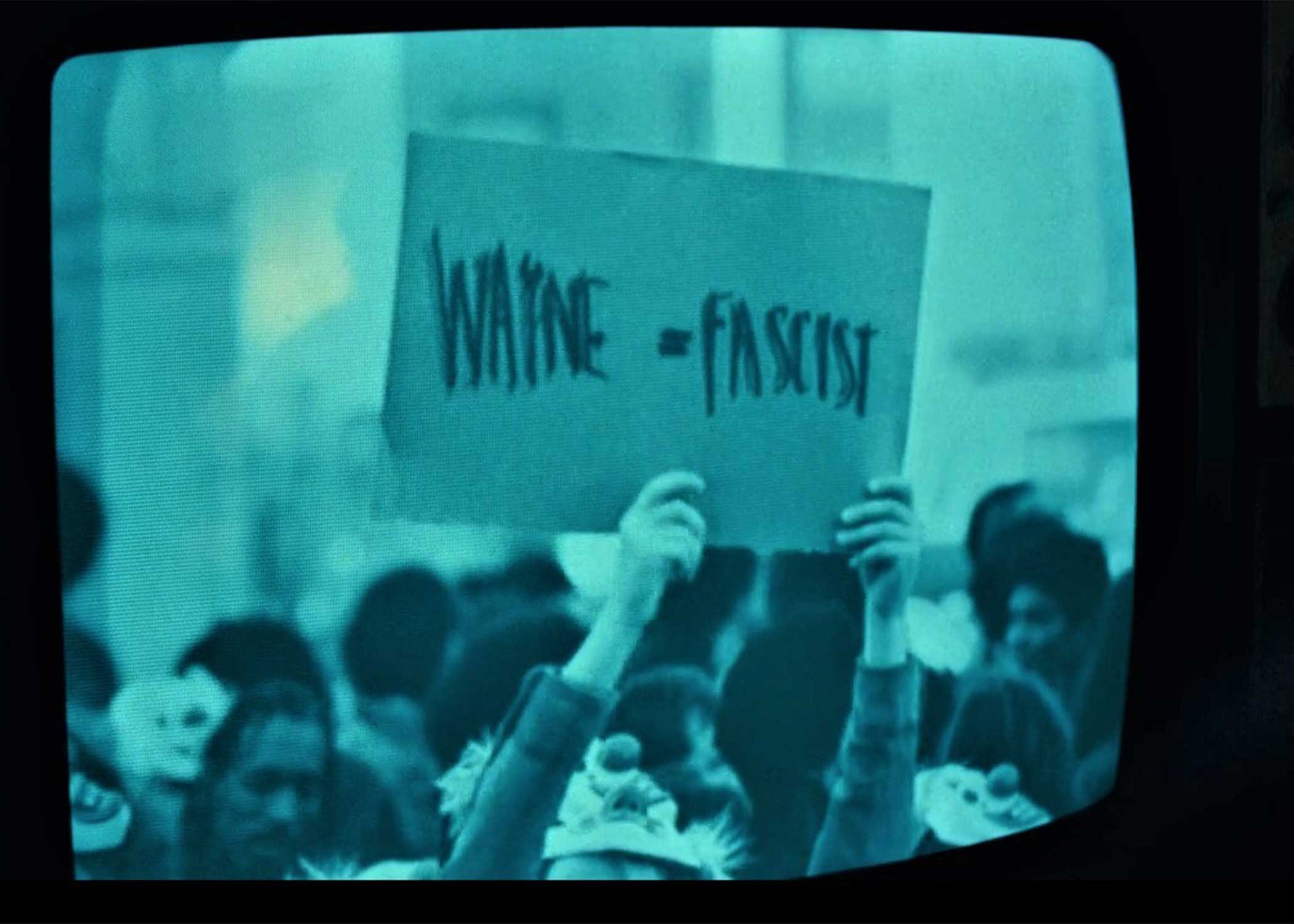

A signs held by a protester in the film which implies the similarities between populists and fascists.

This study of the context and background of the film demonstrates its critical view of late capitalism, the distress it has caused, and the way politics works in it. In the neoliberal era, although they themselves are responsible for the problems in the society, Right-wing populists have the upper hand in politics. In their political campaigns, they promise a bright future and trick people into believing they hold the key to solve their problems instantly. The paradox is that they are conservatives; they want to improve conditions without making structural changes in the system, which seems to be an impossibility. Thomas Wayne is a perfect embodiment of the Neoliberal Right-wing populism; a well-off, white, straight candidate, living in his own ivory tower. He brags about lifting people out of poverty and helping make their lives better. He knows himself “their only hope.” Yet, he denies that underprivileged people have been deprived of some opportunities and thinks protestors who are fed up with inequalities are just “envious of those more fortunate than themselves.” This is probably the truest face of all Right-wing populists in the real world.

At the end, citizens start a collective movement and revolt against “the whole system.” They even kill Thomas Wayne, the one that gives them false hope. On this layer, the film delivers a harsh criticism of the neoliberal system. However, it does not try to say what happens after the riots and never gives a hint of any plan that the people hold as an alternative for the neoliberal system, and in this way the film reduces the political to the sentimental. Here also seems that the film is not an anti-capitalist one.

What Is to Be Understood?

As discussed, Joker is not against the system. But does this mean that it has nothing to give us? Not at all. From this film, one can learn many things about the present world. People related to the film as if they have seen themselves in the mirror. The images in the film are not strange to us: trash everywhere and the city “under siege by sores of rats”, people looking for food in garbage with cats, the funding cuts of social services and limitless privatizations, grudges against the rich, psychologists that want to normalize individuals to fit into the system, naïve people who think “He is the only one who could save the city”, the media that takes the role of a safety valve through which social tensions are released (Murray on TV joking about the mayor’s incompetency), and lonely people who are desperate for a hug, may it be of a fridge.

Joker is not an anti-capitalist film but a smart capitalist one, just as Theodor Roosevelt – the American president during the Great Depression who proposed the new deal not to destroy the system but to save it – was not an anti-capitalist but a smart capitalist. The film warns politicians of the outcomes of the status quo and implicitly invites them to make necessary changes. It reminds us to hold the government responsible for the conditions, something people have forgotten and persist to shift all the blame to their personal incompetency. It also warns the governments of the rebellion and the outrage resultant from their irresponsibility and neoliberal policies. This is emphasized even in the psychological layer of the film. One can say the film is using a conceptual metaphor through which a subject’s relation with the father (’s absence) is illustrated. This is not an over-interpretation. Nations and governments have usually been likened to children and fathers, respectively. Even what George Lakoff presents, in his Moral Politics, is an understanding of how different forms of governments are like different kinds of fathers. In Joker, Arthur and other citizens are ignored by the father/government (its deep impact is vivid when the advisor tells Arthur “They don’t give a shit about people like you Arthur, and they really don’t give a shit about people like me, either.”) and his absence plunges them into chaos. This chaos is the desperate rebellion of those who have been left behind in a landfill as huge as Gotham City, a city taken over by the few rich people bit by bit.

Protesters worldwide in 2019 & 2020 adopted joker’s masks and make-up.

The reaction of the people all around the world to the film was spectacular. In protests against the neoliberal policies of their governments, people – from China to the US – wore Joker masks. If all this makes sense all over the world, and if we relate to Arthur and think we live in the same conditions, it is because – as Bong Joon-Ho in an interview (link in Works Cited) says – “Essentially we all live in the same country called capitalism.”

What Is to Be Done?

This film does not try to answer this question. The movie ends with scenes of demolition, brutality, directionless looting and arson. The outrage, resentment, and disgust of Arthur and the masses with the status quo eventually boils down to insane murderousness. The writer-director Todd Philips does not take the course of movie any step forward. The film ends right in the middle of tumult. It is solely a moral critique of capitalism; it does not come up with an alternative idea or a collective action, there is no intimation of either any political agenda or any specific program of change. The darkness and gloomy atmosphere, the relentless murders, and the violence of the final scenes is precisely the picture that the system tries to present of those in opposition for this is how the system manages to keep itself safe and settled. This film was more, to the writers, a critique of the system by the system to keep away the real critics of the system and nullify their real critiques.

When on the show Arthur says that he is not political, he is right, in this sense that he has no political plan and alternative for the system. But the fact that the neoliberal system has come to a deadlock compels us to think of the possible alternatives. This system can no more satisfy the needs of the people and only adds to the present pile of environmental, social, and political crises. In his Prison Notebooks, Antonio Gramsci once said “The old world is dying away, and the new world struggles to come forth: now is the time of monsters” (267). The truth is that the world is changing and the old order needs to be replaced with a new one. If not, the advent of monsters would be inevitable. These monsters can be Jokers who just revolt violently without any alternatives, as well as politicians who want to keep the unjust system.

One lesson we may learn from history is that in the neoliberal system, when alienated people have trouble finding a job, making money, putting food on the table, and supporting their loved ones, they rarely unite for collective progressive movements. On the contrary, people PRIVATIZE their everything: their anger, pain, fears, and lost hopes. They keep away from the society, stay home and lick their wounds. They lose hope for a better future. And that is the right moment for a monster, a fascist, an opportunist, a right-wing populist to show up and claim to revive people’s dignity and decency if they give her/him power. This is how conservatives, chauvinists, and racists such as Donald Trump are in power all over the world now. People need to go beyond electing these populists/Thomas Wayne-s every four years who will only misrepresent them.

Now ecological crises and a rise of class wars within nations (particularly in the post-COVID-19 era) are the main concerns in the world. Since these are global problems, national mechanisms must be replaced with transnational ones to tackle the condition. Countries need to work collaboratively to save the environment and eradicate poverty. People by demanding radical changes and theorists by theorizing a new world order based on those demands need to cooperate. For the former, we need to demand radical changes in the capitalist production system which is the main cause of the ecological crises; not because it is cool, but because it is rationally prior to anything else. For the latter, the writers believe, at this stage, we need to demand a redistribution of both income and property rights; not because it is moral, but because it is scientifically just. Alongside many civil rights, none of these two demands can be met in the present global capitalism. Now progressive theorists need to unite and devise a theory; the type of theory that – as Karl Marx said – “becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses” (182). For this, this emancipatory theory needs to create a hopeful picture of the post-capitalist future. It needs to be a convincing narrative comprehensible for common people with a wide horizon that can target the demands of as many groups of people as possible.

Works Cited:

Gramsci, Antonio. Prison Notebooks. International Publishers, 1971.

joker is a fresh unsettling brilliant take but that is all it is

https://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/oct/10/joker-far-right-warning-austerity

JOKER Video in Youtube

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Verso, 1991.

Kropotkin, Peter. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. BoD – Books on Demand, 2018.

Lakoff, George. Moral Politics How Liberals and Conservatives Think. The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. Karl Marx, Frederick Engels: Collected Works. Lawrence & Wishart, 1975.

Steger, Manfred B., and Ravi K. Roy. Neoliberalism: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Shahin Ghazaee & Roxana Nejati